Phase Boundaries and capillarity

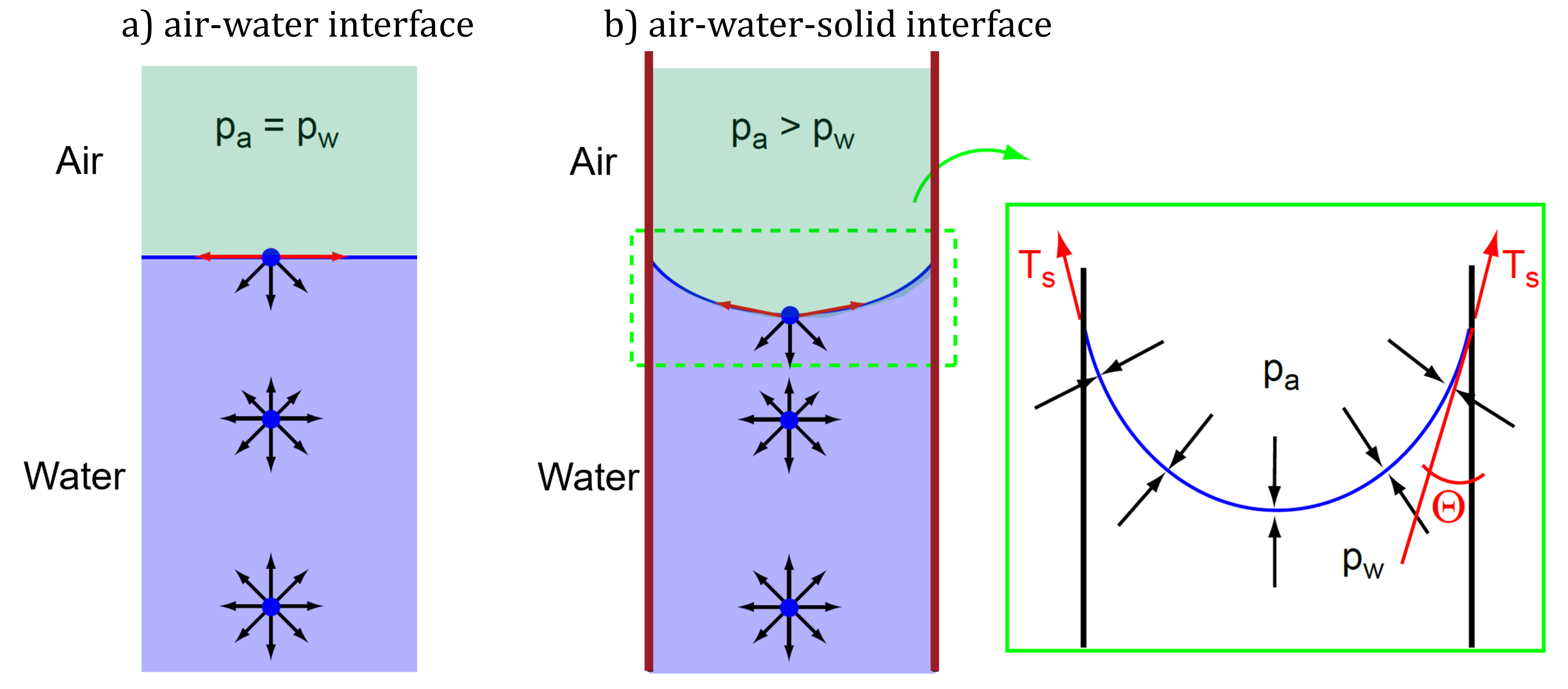

In order to understand the influence of partial saturation on soil behaviour, we first need to better understand the interaction behaviour of the individual phases solid, water and air. For this purpose we distinguish between the interaction at the a) air-water interface and b) air-water-solid interface as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Surface tension phenomenon at a) air-water and b) air-water-solid interface.

Figure 1. Surface tension phenomenon at a) air-water and b) air-water-solid interface.

Water-air interface

Let us first consider the interface between water and air – without any solid as displayed in Figure 1 a). A liquid consists of molecules (blue dot in Figure 1). Attractive and repulsive forces (illustrated as arrows) act between these molecules. Within the volume of a liquid, the forces are balanced. Which is denoted here with arrows of equal length. At the interface between water and air, the density of the water changes abruptly in the range of just a few molecule lengths. This causes the repulsive forces in the water to also increase abruptly.

At the surface of the liquid, the symmetry is disturbed, that is, the molecules at the surface have no neighboring molecules in the vertical direction. With this in the vertical direction, only repulsive forces act on the molecules from below.

To maintain the balance of forces, the repulsive forces in the vertical direction are balanced by attractive forces. The resulting force of the molecules at the surfaces are thus directed inwards. Which then leads to the so-called surface tension \(T_s\) that results in the interface between the water and the air acting like a membrane under tension. Surface tension is measured as the tensile force per unit length of the contractile skin (i.e., units of mN/m). Surface tension is tangential to the contractile skin surface and the reason why water strider can walk on water.

The surface tension \(T_s\) decreases with increasing temperature. The value of \(T_s\) at different temperatures is given in below Table according to Kayne and Laby (1928)1.

| Temperature (°C) | Surface Tension, \(T_s\) in mN/m |

|---|---|

| 0 | 75.7 |

| 10 | 74.2 |

| 20 | 72.75 |

| 30 | 71.2 |

| 40 | 69.6 |

| 60 | 66.2 |

| 80 | 62.6 |

| 100 | 58.8 |

Water-air-solid interface

If the fluids come into contact with solid, three forces have to be considered:

-

First we have the surface tension at the interface between the pore air and the pore water

-

Then we have the attractive forces between the water molecules

-

And third there are adhesive forces acting between the solid and the fluid

If these attractive forces are larger than the others, the resulting forces is upwards directed. Fluids, such as water, where the attractive forces prevail are called wetting fluids. The upwards directed forces pull the water up at the interface to the solid. As a consequence, the interface between the water and the air becomes curved.

And whenever we have a curved surface there is a pressure difference. In this case, the air pressure is larger than the water pressure. The pressures acting on the membrane are \(p^w\) and \(p^a\). The membrane has a radius of curvature \(R_s\) and a surface tension \(T_s\). The horizontal forces along the membrane balance each other. Considering force equilibrium of the curved air-water interface, the pressure difference across the interface is balanced by surface tension forces:

Therein, \(2 R_s \sin \Theta\) is the length of the membrane projected onto the horizontal plane. The angle \(\Theta\) (see Figure 1) is known as the contact angle, and its magnitude depends on the adhesion between the molecules in the contractile skin and the material to which the fluid (water) is in contact. Following above equation, the pressure difference \(p^a-p^w\) is

where, for the 3D case, the radii of curvature of a warped membrane in two orthogonal principal planes are assumed to be identical, i.e. \(R_1=R_2=R_s\). For this pressure difference to develop, the pore water needs to rise in the tube such that a negative water pressure acts. This is the physical cause of the capillary rise of water in the soil.

Capillary rise

The capillary phenomenon is associated with the pressure difference \(p^a-p^w\). To introduce the concept of capillary rise, consider glass tubes of different diameter inserted into water under atmospheric conditions as displayed in Figure 2.

Water rises up in the tubes as a result of the surface tension of the contractile skin and the tendency of water to wet the surface of the glass tube. Capillary behavior can be analysed considering the vertical force equilibrium of the capillary water in the tubes:

The vertical component of surface tension \(F_{Ts,v}\) is responsible for holding the weight of the water column \(W_w\), which has a height \(h_c\). Above equation can be rearranged to give the maximum height of water in the capillary tube:

Considering that \(R_s = r/ \cos \Theta\), with the radius of the tube \(r\), the maximum capillary height is given by

From above equation it is clear, that the maximum capillary height depends on the radius (diameter) of the tube: the capillary height increases as the tube radius gets smaller.

If instead of a tube with constant diameter a so-called Jamin-tube with variable diameter is used for this experiment, it will be observed that the capillary height is different for wetting and drying processes. This effect is illustrated in slides 3 and 4 of Figure 2. When the end of the Jamin-tube is immersed in water, the water level in the tube rises to a height corresponding to the capillary rise height of a pipe of diameter \(d_2\). On the other hand, if the pipe is completely filled with water, the water level will fall to a height corresponding to the capillary rise height of a pipe of diameter \(d_1\). The capillary head during drainage is therefore determined by the small cross-sections, whereas the wide cross-sections determine the behaviour during wetting.

The capillary rise is different for the wetting and drying processes due to variations in capillary pore size.

Analogy to soils

The obvious question at this point is: Why are we concerned with water rise in tubes?

The structure of soils is very complex and difficult to describe in all its details. In a simplified consideration, we can think of the pore space in the soil as an assembly of tubes with very different diameters. From above observations, we can conclude that in narrow pore channels the water will rise higher than in pore channels with larger diameters. Empirical values for the height of capillary rise in natural soils during wetting or drying events are provided in below tables.

| Soil | Grain size (in mm) |

Capillary height \(h_c\) (in m) |

|---|---|---|

| Sand | 2.00 - 0.60 | 0.03 - 0.10 |

| 0.60 - 0.20 | 0.10 - 0.30 | |

| 0.20 - 0.06 | 0.30 - 1.00 | |

| Silt | 0.06 - 0.02 | 1.00 - 3.00 |

| 0.02 - 0.006 | 3.00 - 10.00 | |

| 0.006 - 0.002 | 10.00 - 30.00 | |

| Clay | < 0.002 | > 30.00 |

| Soil Type | Capillary Height \(h_c\) (in m) |

|---|---|

| Medium to Coarse Gravel | 0.05 |

| Sandy Gravel or Fine Gravel | ≤ 0.2 |

| Coarse Sand or Silty Gravel | ≤ 0.5 |

| Medium and Fine Sand | ≤ 1.5 |

| Silt | ≤ 5 |

| Clay | up to > 50 |

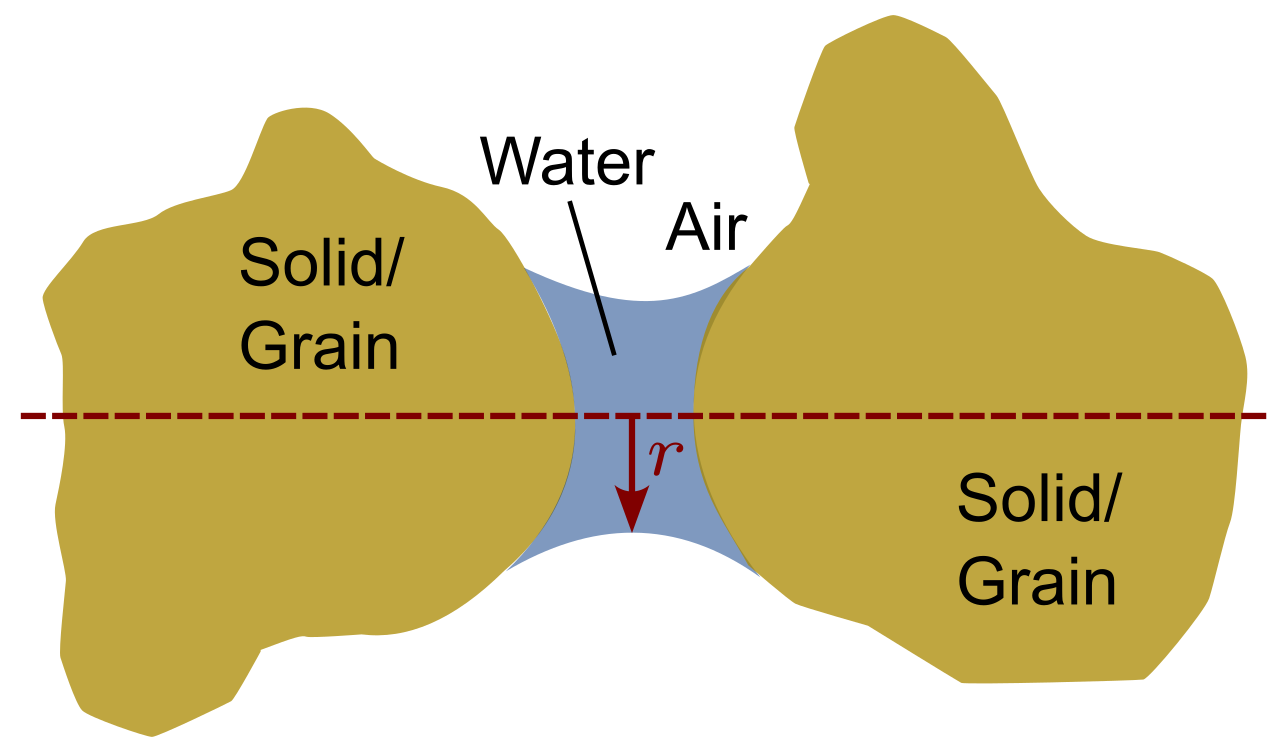

Surface tension has the ability to support a column of water, \(h_c\), in a capillary tube. The surface tension associated with the contractile skin places a reaction force on the wall of the capillary tube. The vertical component of this reaction force produces compressive stresses on the wall of the tube. The interface behaviour from the water column and the tube transfers to the interface behaviour of pore water and soil particles. Similar to the menisci at the interface between the tube and the water, menisci between the particles and the pore water form:

Figure 3. Water menisci between two soil grains

The compressive stresses acting on the wall of the tube translate to an increase of the grain-to-grain forces and thus an increase in effective stress. Consequently, the presence of capillary pressure \(p^c=p^a-p^w\) in unsaturated soils produces a volume decrease and an increase in the shear strength of the soil. The extent of the additional effective stress due to the water in the contact zone between the two grains is discussed in the following section.

References

-

Kaye, G. W. C., & Laby, T. H. (1928). Tables of physical and chemical constants and some mathematical functions. Longmans, Green and Company Limited. ↩

-

Y. Mualem, ‘A new model for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated porous media’, Water Resources Research, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 513–522, Jun. 1976, doi: 10.1029/wr012i003p00513. ↩

-

M. Th. van Genuchten, ‘A Closed-form Equation for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils’, Soil Science Society of America Journal, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 892–898, Sep. 1980, doi: 10.2136/sssaj1980.03615995004400050002x. ↩